What’s in the water? Microorganisms in recreational waters

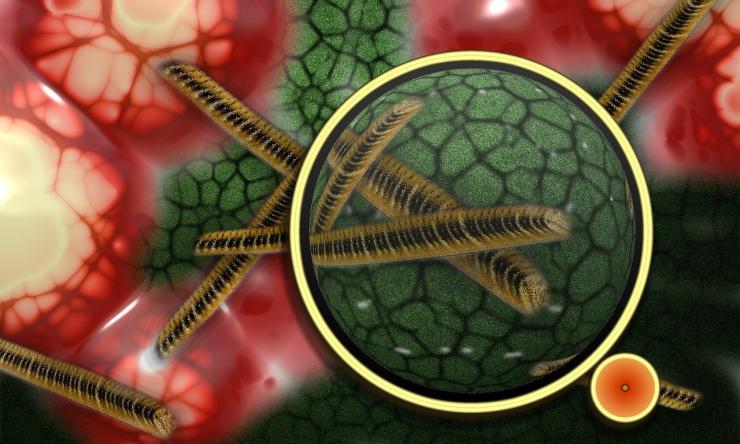

As people flock to communal pools, water parks, beaches and lakes to find relief from the summer heat, some may be unaware of the microscopic hazards lurking in these waters. An expert with Baylor College of Medicine shares information about common microorganisms that can have an impact on your health.

“There's a variety of microorganisms that can make recreational activities in water less than fun,” said Dr. Stacey Rose, associate professor of infectious diseases at Baylor. “Microorganisms thrive in every type of water, and infections will impact everyone differently.”

Recreational swimming has been linked to infections with harmful bacteria, viruses and parasites, including outbreaks of Cryptosporidium, Legionella, norovirus, and Giardia. People with compromised immune systems or open wounds are not recommended to swim in shared water environments as they are at a higher risk of becoming infected. Those with open wounds also have a chance of shedding harmful bacteria and spreading them to others. Infection can lead to diarrhea, skin rashes, ear pain, cough or congestion and eye pain, which could be mild, moderate or severe.

Although pools and water parks are treated with chlorine to kill harmful microorganisms such as E. coli, frequent use by multiple swimmers can introduce new microorganisms or increase the levels of microorganisms already in the water, decreasing the effectiveness of the chemical. Additionally, some microorganisms like Cryptosporidium can be resistant to chlorine due to their natural durability.

Rose also stresses that people who have experienced diarrhea should avoid swimming in public waters for at least two weeks.

“You can shed microorganisms like norovirus or E. coli for several days, sometimes weeks after diarrhea has subsided,” said Rose. “Children who still wear diapers are at a high risk of spreading these bacteria, so bodies of water designed for babies and toddlers often have higher than usual amounts of fecal matter.”

People will also flock to fresh and saltwater for relief from the heat, both of which have their own hazards. Rose says that in freshwater, Naegleria fowleri, commonly known as brain-eating ameba, can be present, but it is uncommon. “A great prevention technique is pinching your nose closed when diving in to prevent water from going directly into your sinuses and infecting you,” Rose said.

In the Gulf of Mexico and brackish water, Vibrio vulnificus is a microorganism that is often reported during the summer months. Those with liver disease and other immune compromising conditions are at highest risk for Vibrio infection.

Microorganisms may be small, but preventative strategies can have a big impact, Rose said. After you swim, rinse off with a shower. If you are worried about the cleanliness of the water, you can purchase test strips that analyze chlorine levels. Look around at the environment and see if there are any characteristics that give you pause, such as foul smells coming from the water, discoloration or cloudy water, or drainage pipes close to or in the water. If you own a pool, be sure to follow proper maintenance and cleaning schedules before inviting others to swim.

“Think of swimming hygiene as a two-way street — by taking the right precautions, you protect yourself and in turn protect others,” Rose said.