Pancreas cysts come in a wide variety. Many times, they cause no symptoms and are accidentally discovered when imaging is done for some other reason. In other cases, pancreas cysts can cause abdominal pain or fullness. Some pancreas cysts are harmless and never turn into cancer and can be ignored. Others may change into cancer and need to be monitored. Other pancreas cysts have a higher chance of becoming cancer and need to be removed.

Your doctors will use various tests including CT scans and MRI scans to obtain more information about your pancreas cyst. Sometimes the fluid in the cyst is sampled using a test called endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration or EUS-FNA. In this procedure, a flexible scope is placed into your stomach to guide a needle into the cyst to obtain fluid for analysis. The information from these tests helps your doctors determine what type of cyst you have and whether it should be removed or if it can be safely monitored.

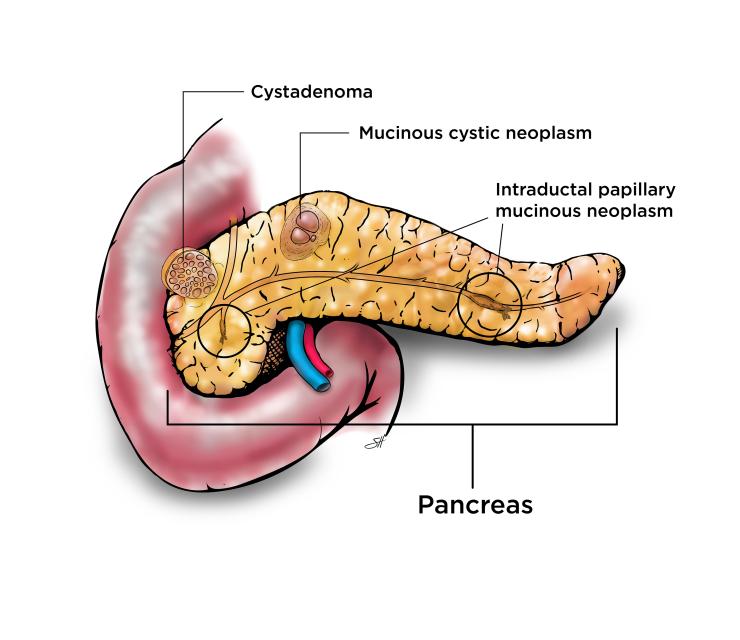

Cystadenoma

Serous cystadenomas are essentially considered benign tumors that do not turn into cancer. These cysts are not removed unless they grow large enough to cause symptoms such as pain. Sometimes very large cystadenomas in the head of the pancreas can block the bile duct or the outlet of the stomach. Cystadenomas that cause symptoms can be cured by removing the cyst but most of these cysts do not cause symptoms and are not removed.

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm (MCN)

Mucinous cystic neoplasms are premalignant meaning they can change into pancreas cancer and should be removed. They are more common in women and usually found in the body or tail of the pancreas. These cysts are filled with fluid that is thick like syrup. These cysts do not connect to the pancreas duct. Surgery to remove these cysts is highly successful, particularly if removed before the cyst changes into cancer.

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm involves the lining of the pancreas ducts, or the tubes that carry the digestive juice from the pancreas to the small intestine. These cysts are bump-like growths on the lining of the pancreas ducts that can turn into pancreas cancer if not removed. The exact cause is not fully understood, but they occur more commonly in people over the age of 60, smokers, patients with chronic pancreatitis and specific genetic conditions or mutations.

There are two types of IPMNs; main-duct type and branch-duct type:

Main-duct

- Involves the main pancreatic duct.

- Has higher risk of developing into pancreas cancer (40-60%).

- Typically removed with surgery.

- Areas of the pancreas that are not affected are not removed but ongoing surveillance follow up is recommended to monitor the remaining pancreas after surgery.

Branch-duct

- Involves the smaller side branches of the main pancreatic duct and usually involve a smaller portion of the pancreas.

- Lower risk of changing into cancer (10-15%).

- Your surgeon will look at the size of the cyst(s), presence of a dilated main pancreas duct, solid component or nodule and features of the biopsy to determine the risk of it changing to cancer.

- Many branch-duct IPMNs are watched and never removed.

- Your surgeon will discuss the risk and benefits of surgery versus continued observation.

Credit

Credit